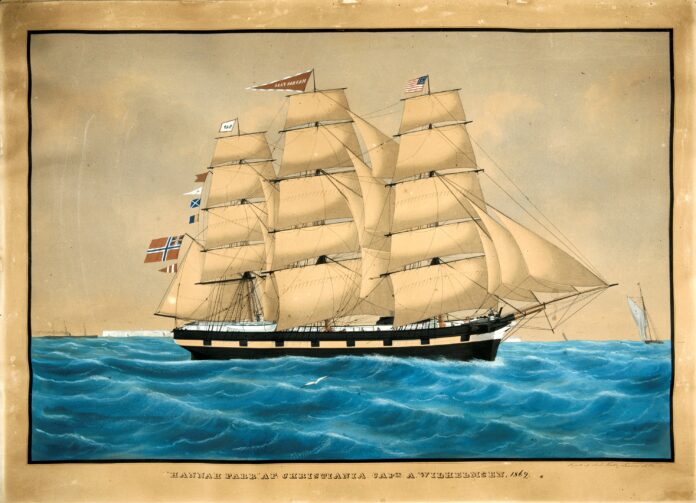

THE Norwegian emigrant ship Hannah Parr set sail from Christiania (now Oslo) in Norway on April 12, 1868, bound for Quebec, Canada. Aboard were 366 hopeful emigrants, ranging in age from babies to a 74-year-old passenger, as well as a dedicated crew, writes Limerick historian Sharon Slater.

The voyage was initially expected to take 51 days, carrying its passengers toward a new life in North America. However, fate had other plans. Just two weeks into their journey, a severe storm struck, dramatically altering their course and extending their passage to an astonishing 107 days.

As the Hannah Parr traversed the Atlantic, it encountered an intense and relentless storm. The ship suffered significant damage, with the mast and steering devices rendered nearly useless. The crew, displaying remarkable ingenuity and resilience, managed to strap together a makeshift sail to regain some control. Their immediate goal became reaching the nearest port for repairs — Limerick, Ireland.

On May 7, 1868, after a harrowing experience at sea, the ship reached the Shannon Estuary, anchoring near Scattery Island before making its way to Limerick. The ship had arrived “dismantled, with loss of sails” and had been towed into the city’s floating docks for much-needed repairs.

The passengers and crew of the Hannah Parr were fortunate to have reached a city known for its generosity. The Norwegian consul, Mr. M. R. Ryan, took immediate steps to ensure the emigrants’ welfare. The ship was placed under the care of Messrs Ryan, Brothers, & Co., who oversaw the repair efforts with great urgency.

Limerick quickly rallied to support its unexpected visitors. A local woman, Anne Kearse, played a crucial role in assisting the Norwegian emigrants, appealing to the public for donations of money, food, and clothing. Her efforts did not go unanswered, as many citizens contributed to the cause. Anne was the widow of Thomas Kearse, a merchant tailor who died seven years before the arrival of the Hannah Parr. She was residing at 28 George Street in 1881, when she died aged 68 years.

During their stay, the emigrants were treated to musical performances, including an evening at the Protestant Orphan Hall, where they listened to hymns sung by the residents of the female Blind Asylum. Such acts of kindness helped ease their anxieties and provided moments of peace amid their disrupted journey.

Though the emigrants received warm hospitality, their time in Limerick was not without sorrow.

During the repairs, three children succumbed to illness. Several deaths had also occurred earlier on the voyage, but new life emerged as well, with several births recorded aboard the Hannah Parr. The deceased children were laid to rest in St Munchin’s churchyard at the Kearse family grave. In 2008, the Limerick Civic Trust placed a memorial plaque in honour of the lost children, ensuring that their brief lives would not be forgotten.

Unlike many emigrant vessels of the time, where passengers often suffered from neglect, the Hannah Parr was subject to strict oversight. The Norwegian government had put regulations in place to protect its emigrants, requiring the ship’s owner to deposit a security sum of £2,000 to ensure the passengers were well cared for. A doctor and a Swedish government agent were present on board, overseeing provisions and medical care.

This level of responsibility stood in stark contrast to the experiences of many Irish emigrants, who often faced appalling conditions at sea. Infamous ship-owners, such as Limerick’s Francis Spaight, had profited from clearing famine-stricken tenants from their lands, packing them onto ships with little regard for their well-being. In 1847 alone, he used the government grant scheme to clear over a thousand people from his lands by the shore of Lough Derg.

Work on the Hannah Parr proceeded rapidly, with significant effort put into refitting the damaged vessel. The original foremast was found to be beyond repair, requiring a new one to be procured from Cork. The sheer scale of the timber, weighing several tons, underscored the severity of the damage sustained in the storm.

During this time, the emigrants found temporary shelter in a docking shed, returning to the ship only when it was deemed safe. This period of enforced delay, while frustrating, allowed them to experience Limerick and form unexpected bonds with the local population.

On June 9, 1868, after over a month in Limerick, the Hannah Parr was finally ready to continue its journey. That morning, at around eight o’clock, the ship left the dock, towed by two steamers, the Privateer and the Bulldog, down the River Shannon toward Foynes. A large crowd gathered along the shore to bid farewell, cheering as the vessel made its way out to sea. The emigrants, deeply moved by the kindness they had received, responded in kind, waving and calling out their thanks.

A particularly poignant moment occurred as one elderly Norwegian man prepared to board. Overcome with emotion, he turned to the well-wishers and handed his pocketbook to a gentleman, motioning for him to write something as a keepsake. The gentleman inscribed a heartfelt message:

“God bless the Hannah Parr with her living freight, and bring them through a speedy and prosperous voyage to the land of their adoption; and bless them abundantly for time and eternity.”

Before their departure, the passengers penned a letter expressing their deep appreciation for Limerick’s hospitality. Though written in imperfect English, their heartfelt words conveyed profound gratitude:

“Before we leave this city and its exceedingly friendly population, it is our wish to express our hearty thanks for all the kindness the ladies and gentlemen of Limerick have shown us. With sorry hearts we came as shipwrecked to the coast of Ireland; but we came up the Shannon and saw the beautiful land on both sides, and we then felt that the good God had not yet left us. In this pretty land we also met people who took a great deal in our sorry – who strained to give all the animation as possible – who, by gifts of Christian books and speaking friendly to us, laboured to open our hearts for the grace of God – who took us in their houses and treated us with friendship and honour; all this has affected our hearts, and we never shall forget it.”

After leaving Limerick, the Hannah Parr remained in Foynes for a few days before setting sail once more. She finally arrived in Quebec on July 28, 1868. Their safe arrival was reported back in Limerick on August 15, bringing closure to a journey that had lasted far longer than expected.

The following month, a letter arrived from the ship’s captain, expressing thanks to the people of Limerick for their kindness. Though the Hannah Parr’s passage had been fraught with difficulty, it had also become a testament to the compassion and resilience of those who found themselves unexpectedly brought together by fate.