IT IS well known in Limerick that the very first permanent outside sculpture to Irish politician Daniel O’Connell was the very one located right in the centre of The Crescent. This bronze statue atop a granite podium was unveiled in 1857, 10 years after O’Connell’s death. It was designed by John Hogan and cost £1,300.

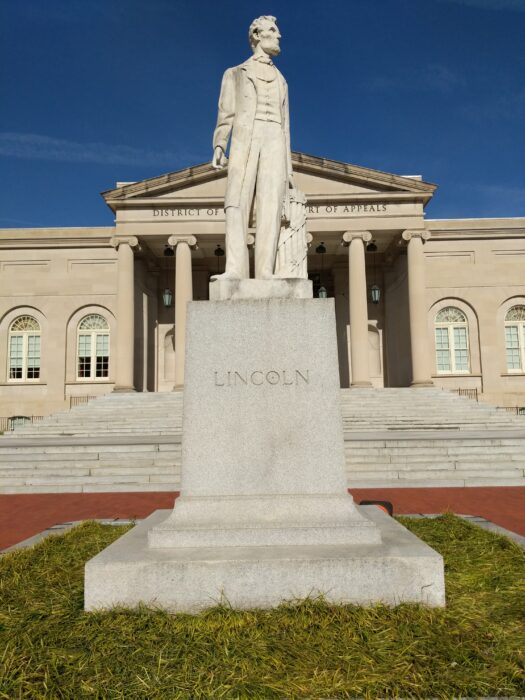

However this was not the only sculpturing first for a political liberator with a link to Limerick. 10 years later, in 1868, the oldest extant statute to United States President Abraham Lincoln was unveiled outside City Hall in Washington DC. The sculptor was Limerick born Lot Flannery.

Although the city council in Washington resolved to have a memorial erected within a few days of the Lincoln’s death, they were not the first to have one erected. That claim goes to San Francisco, where, in 1866, they erected a monument made of plaster which was later replaced with a metal statue. Unfortunately this was destroyed during the firestorm that followed the 1906 earthquake, leaving the statue by Lot Flannery to be the oldest still standing.

Lot Flannery, the son of Ellen Corbett and Patrick Flannery, left Ireland as a child during the Great Famine. His talent as a sculptor was known from an early age as he travelled back from the United States to Europe to hone his skills before returning across the Atlantic once more.

Lot and his brother Martin set up one of the largest stone carving businesses in his adopted city of Washington DC. Both Lot and Martin were conscripted into the Union Army in July 1863.

His business flourished and he became an ingrained member of society in the US capital, even if he did not appreciate it.

An obituary in the Washington Evening Star of December 19, 1922, gave an insight into Flannery’s personality. He was called “an individual all himself and was a man who shunned publicity, often avoiding people for this reason. He never joined any clubs or associations but was merely content in carrying out his own work.”

Despite this, Flannery became good friends with Abraham Lincoln. The Washington Times of December 19, 1922, noted that “Lincoln often visited young Flannery in his studio on Massachusetts Avenue and they took long walks together.” Perhaps Lincoln appreciated the company of a man who kept himself out of politics.

Flannery, like so many of his counterparts, was in attendance at that fateful night in the Ford Theatre when President Lincoln was assassinated. He recalled that he arrived early and saw the President take to his box. He was in the crowd that heard the shot and felt the commotion as the injured president was ushered out of the building to a nearby house, where he ultimately passed way from his wounds.

It was out of this tragedy that a committee of Washingtonians was created to erect a monument to the slain President. After deliberations, Flannery’s marble design was unanimously chosen. It cost $25,000 to create and the funds were mostly raised by subscription, with the largest contribution from John T Ford, the owner of the Ford Theatre.

On the third anniversary of Lincoln’s death, April 15, 1868, Flannery’s statue was unveiled. Not only does it stand as the earliest extant memorial but also as the only memorial created by someone who knew the late President. Over 15,000 people showed up for the unveiling, including dignitaries President Andrew Johnson and General Ulysses S Grant.

The statue has been removed and rededicated twice. The first in 1919, during renovations of City Hall. Following an outpouring of support from citizens and a veterans group, the statue was restored and rededicated in 1923. This took place shortly after Flannery’s death in December 1922. His obituary in the Washington Times said that “his statue of Abraham Lincoln rescued from the oblivion of a storage room but a few weeks ago and replaced in front of the city hall …. sculptor, individualist and of late years recluse, died at his home this morning as peacefully as though his last wish had been fulfilled”.

It previously stood on a five-and-a-half-metre column on top of an almost two-metre octagonal base, which Flannery purposely arranged as to “place him so high that no other hand might strike him down”.

After a three-year remodelling of the old City Hall, the second rededication took place in 2009, where it rests on top of an octagonal base.

Flannery’s work yard often drew the attention of Washingtonians who passed by daily. They would glance at the headless, armless figure who stood partially hidden by trees for almost 50 years. This figure was originally brought back intact to the United State from Athens by a Commodore Boyle of the United States Navy and placed above the entrance to his brother’s hotel in Virginia. One night, some Union soldiers while under the influence pulled it down with a rope, smashing the head and arms. It was removed to Flannery’s yard, where it stood in silence.

In 1915, Flannery was asked by a journalist from the Stevens Point Journal if he ever thought of repairing the head and arms, to which he responded: “No, no. That would be cruel.”

Although he did not carry out the creation of headstones with his brother, he was commissioned to create memorials. In June 1864, 21 women, mostly Irish immigrants, were killed after ceramic shells left in the sun to dry ignited, causing the exposed gunpowder the women were using to fill cartridges to explode. Flannery created the Arsenal Monument known as “Grief” at the Congressional Cemetery, which was unveiled on the first anniversary of the disaster. This too was set on a high pillar and depicted a woman in mourning.

As the cityscape evolves and generations pass, Flannery’s handiwork in Washington DC remains steadfast, a testament to the enduring bond between artist and subject, immigrant and adopted land.

His journey from the famine-stricken Ireland to the bustling streets of a nation’s capital epitomises the immigrant spirit and resilience.

Flannery’s artistry, borne of talent and honed through dedication, graced the city with monuments that transcended mere stone. His sculptures, from the enduring visage of Abraham Lincoln to the solemn grace of “Grief”, bear witness to his craftsmanship and vision. His presence lingers, a silent witness to the triumphs and tribulations of the American Civil War.