MARKING Breast Cancer Awareness month, a lead doctor has thrown light on what happens when a patient presents with what might be a problem.

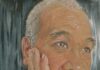

Dr Máire Lavelle, consultant pathologist at University Hospital Limerick, says that the most common question women ask is what happens after a scan reveals something out of the ordinary.

Dr Lavelle explained that her role in the diagnosis of disease and treatment options for women attending the region’s Symptomatic Breast Unit, chiefly in helping to “diagnose breast disease under the microscope”.

“When a patient comes to the breast unit with a problem, they see a surgeon who takes a clinical history and examines them. If necessary, the surgeon may request a scan.

“If the radiologist performing the scan sees something abnormal, they will take a biopsy of it – which a tissue sample of the abnormal area of the breast which is put in a container of fixative and sent to the histopathology laboratory.”

Dr Lavelle explained that the sample then undergoes a process which involves fixing the tissue sample in formalin in its container, before it is then embedded in a small cassette and covered in paraffin wax, creating a wax block.

“The tissue is cut into extremely thin strips by a medical scientist on a machine called a microtome. The thin strips are placed onto a glass slide,” Dr Lavelle explained.

“At this point, the cells are still difficult to see because they are very transparent, so the slide goes through a staining machine where tissue dyes are applied to the sample which colour the cells so they can be seen. The dyes used are haematoxylin and eosin, which dye the tissue in pinks, blues, reds and purples.

“The glass slide is dried and then a glass coverslip is glued onto the top of the sample, so the sample is trapped firmly between two slides of glass.

“This is the point when I can put the slide under the microscope and make an assessment.”

Dr Lavelle said that sometimes she “can make an immediate diagnosis. Sometimes the interpretation is more complex and I might need to perform more chemical tests on the sample to establish a diagnosis.”

“Even if the sample is clearly cancerous, I may still need to perform more tests to establish the subtype of cancer and what hormones it expresses. All these extra tests allow decisions to be made on potential future surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy.”

Dr Lavelle also takes part in discussions in multidisciplinary meetings.

“Surgeons, radiologists, pathologists, oncologists, radiation oncologists, and breast care nurses all attend these meetings and we each discuss our findings to establish the diagnosis for the patient and discuss the treatment options for each patient.”

She says her job also involves cancer research as well as education and training of medical students, junior doctors, and medical scientists.

When asked about her favourite part of her work, she says that “pathology is often described as ‘the bridge between science and medicine’ and I really enjoy having a hand in both fields. There is huge job satisfaction in being part of the breast team to treat patients with breast cancer. That is why I became a doctor, to help people.”