The short answer is probably not. Certainly not with the limited information to hand at the very least. However, addressing vacant homes is one part of an overall solution made up of many different mechanisms.

It’s often quoted that there are 166,752 vacant homes in Ireland. This is correct, once caveated with “as per census collection night”. That’s an important point to note.

This figure is not a running total regularly monitored by the CSO, but it does represent a point in time. The actual definition of ‘vacant’ for the census is “a vacant dwelling is a point in time indicator taken on Census Night as to whether the property was inhabited or not on Sunday 3 April 2022.”

However, while it is correct that there are around 167,000 vacant homes in Ireland, this figure is often quoted as if all these homes are readily available for new people and families to move into.

This is far from reality.

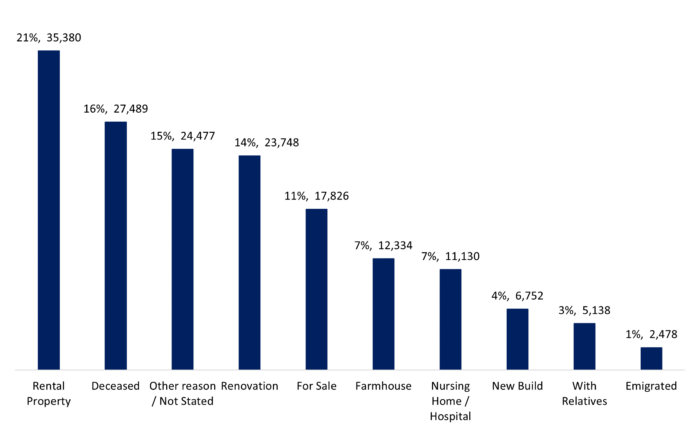

Let’s have a look at the reason for vacancy to start. The graph below provides an overview of why homes might be vacant.

35,380, or 21 per cent, of homes are rental properties – the ‘rental property’ category contains dwellings that were advertised as being for rent at the time of the Census, as well as short term lettings and properties that were between lets but not currently advertised.

The next most common category involved the owner being deceased (27,489 homes).

The “other reason” (24,477 homes) is where enumerators could not clearly ascertain a reason for vacancy.

23,748 homes were under renovation.

The above should serve to inform people that it is likely just a small number of vacant homes are available for occupation in the short term.

The family of recently deceased people deserve to have time to grieve, therefore it is likely not appropriate for these families to immediately release the home to the market – though more research could be carried out on the length of time vacant.

Furthermore, there is a significant number of people in nursing homes or hospitals, would it be appropriate to use this home in the interim? Likely not.

The point is, removing most of the categories that aren’t appropriate (also including ‘other reason’, ‘living with relatives’, and ‘emigrated’) leaves us with in the region of 32,000 homes at a national level.

To put it into perspective, 32,000 is less than one year of the annual supply of homes that Ireland needs – so at best, opening up these properties might just buy some time and nothing more.

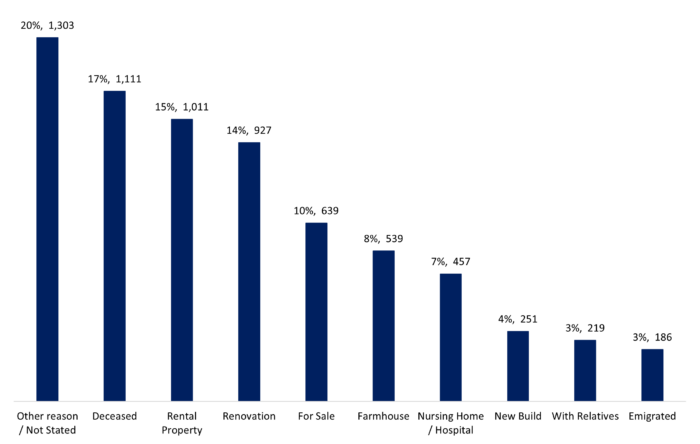

Let’s bring it a bit closer to home. For Limerick, there were 6,643 vacant homes.

The Limerick data follows an almost identical trend as the national data. Deceased owners, rental properties, renovations, farmhouses, owners in care, and new builds account for almost 75 per cent of homes.

That leaves around 1,708 homes that might be potentially fit for being occupied in the short term. Again ignoring why someone may be living with relatives.

To again put that into perspective, the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) outlines Limerick needs approximately 1,800 homes per year.

So again, we’re buying time.

By the time the existing stock of vacant homes would be released to the market (hypothetically), it would be a one-off impact until that stock built up again.

Therefore, when advocating for better housing, it isn’t as simple as outlining that there are 167,000 vacant homes available in Ireland. In the overall conversation, we can call for more targeted measures when speaking about vacant homes that will actually progress housing policy.

Firstly, we need to actually understand how many homes are available to be released / bought / rented by other occupiers. That means going down through the categories listed above and seeing what is and isn’t appropriate.

This includes more of an effort to understand the ‘other reason’ section too.

From that, we need to look at where these remaining homes are located. are they close to public transport? Are they close to schools? Medical services? At the moment, we don’t know. And to make a place a home, this supporting infrastructure has to be in place.

Lastly, we actually need to know what the quality of this accommodation is and how much work would need to be done to make these livable for people.

It all comes back to supplying new and affordable homes and delivering those on a yearly basis.

Of course, targeting vacant homes has its place and they shouldn’t be allowed to fall into dereliction – especially when trying to increase the vibrancy of an area. But it’s far from the panacea that it is often made out to be when speaking about impactful solutions to the current crisis (or emergency!).