Limerick Chamber’s Spring 2022 economic update for the Mid West outlined a broadly positive picture with a record number of people in employment, strong graduate numbers, and high business confidence. However, one downfall across the Mid West, and indeed Ireland, to nobody’s surprise, is the housing landscape.

Simply put, it is not where it needs it to be. This first in a series of housing articles gives an overview of home delivery, the key players / strategy and potential issues with forecasting demand.

Future articles will focus on purchasing, renting, a more in depth look at Housing for All and its mechanisms, and potential solutions from abroad.

Home Availability and Delivery

Some of the high-level findings of Limerick Chamber’s report launched this spring outline that there were 25 residential homes to rent in Limerick City and Suburbs in April across the main rental platforms.

In May this increased to 48, but has been on a downward trend since with 40 homes available in June and 31 available in July.

The average rent for these 31 homes in July was €1,641 while the median was €1,550. Of those homes on the market to rent in July, five homes were one-beds.

This signals that smaller homes for single people or smaller families are difficult to come by. Trying to rent sustainably is also a potential issue, with six of these homes obtaining a BER rating of B or A – with the remaining homes either being excluded, being rated C or below, or no BER rating provided.

Across the Mid West in 2021, 1,323 houses were delivered – comprising of 600 homes in Limerick, 412 in Clare, and 311 in Tipperary. This represents a total Mid West increase of 116 homes in 2021 over 2020 (+88 in Limerick, +18 in Clare and +10 in Tipperary). This increase in 2021 is unsurprising given the impact lockdown had on construction sites in 2020.

The Mid West has delivered an additional c. 330 homes in the first half of 2022 compared to 2021, which is welcome news.

Overall, the Mid West, and its constituent counties, have been on an upward trend of delivering homes for the last several years, albeit not reaching the levels that they need to.

It is important to note that there are many different actors in the market for new homes (self-builds are counted in total delivery but often don’t come to market).

For example, there are three main types of home purchasers; owner occupiers (first time buyers and people moving house, ultimately people buying to live in the homes), the state (for the provision of social housing) and investors.

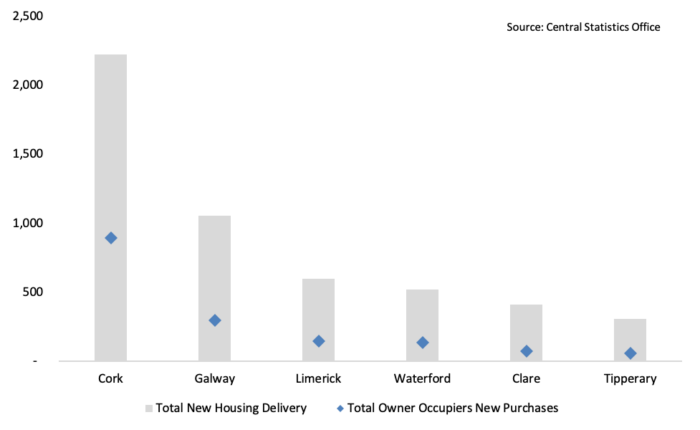

Fig 1.1 below plots the total number of new homes delivered versus the number of new homes purchased on the market by owner occupiers. It allows us to understand how many new homes delivered actually go to owner occupiers.

For example, out of the 600 homes delivered in Limerick in 2021, 148 of them went to owner occupiers.

In Clare and Tipperary, 74 and 57 went to owner occupiers respectively. While increasing the total number of homes delivered is extremely important, ensuring an increase in the number of homes available for purchase by owner occupiers is critical. Currently there is competition between the three main purchasers in the housing market, with owner occupiers not having the same level of purchasing power as the state and investors.

The Mid West had a wealth of home planning permission grants in the system in 2021, however, the key is activating these planning permissions and turning plans into bricks and mortar. The granting of planning permissions is no guarantee that homes will be commenced.

In 2021, the Mid West saw 2,834 homes granted planning permission, 675 (24 per cent) were apartments. In Q1 2022, 966 homes were granted planning permission across the Mid West, compared to 377 in the same period in the previous year. A substantial increase.

In a way, planning permission data can give a false sense of security when trying to estimate future home provision with the key metric being commencements and delivery.

Forecasted Demand

The Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) calculated under a high international migration scenario, Ireland would need 33,000 homes per year – or 28,000 just to keep in line with population growth.

The annual demand in Limerick is forecasted to be c.1,200 to c.1,800 new homes per year (depending on the scenario). This represents a doubling or tripling of its existing housing output. At the same time, Clare needs c. 450 to c. 660 homes per year and Tipperary needs c. 680 to c. 930 which, again, represents a doubling or tripling of existing delivery.

Each year of missing this target adds more delivery needed in future years. However, the Mid West is not alone in grappling with these issues.

In 2021, Galway delivered 1,055 homes with the ESRI calculating the need for c. 1,393 to c. 2,065 homes. Cork delivered 2,226 in 2021 but need an annual delivery of c. 3,505 to c. 3,849. In 2021, Waterford delivered 521 new homes but need 652 to 626 per year, as per the ESRI.

The above demand projections do come with some caveats. The analysis undertaken by the ESRI accounts for future population growth and does not account for pent up demand (something that can be very hard to accurately measure).

That is to say, adults living with their parents etc. are not included in the analysis. Therefore, it would be prudent to assume the actual demand for homes in the coming years is higher than forecasted.

Other organisations like the National Asset Management Agency (NAMA) outline housing need could be as high as between 38,000 to 61,000 per year.

Pent-up Demand

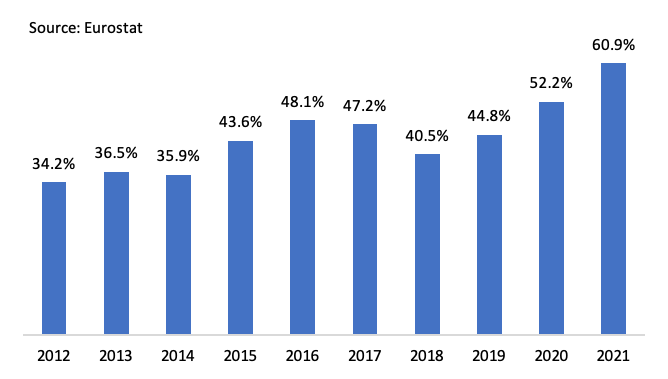

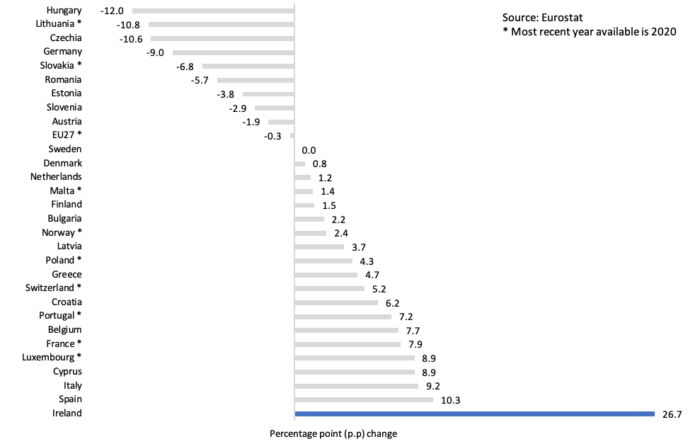

To identify one strand of the potential scale of pent-up demand, the percentage of young adults (aged 25 – 29) living with their parents gives an indication (Fig 1.2 below).

From 2012 to 2021, the share of young adults living with their parents in Ireland almost doubled from 34.2 per cent to 60.9 per cent – an increase of 26.7 percentage points (p.p).

To put this into perspective, the Central Statistics Office (CSO) estimates that there were almost 300,000 people in this cohort in Ireland in April 2022. A rough estimate could indicate almost 183,000 people aged 25 to 29 are now living with their parents.

The number of people living with their parents could have been exacerbated by people moving home during the covid period. However, as the graph below outlines, the share has been mostly on an upward trend for the last several years – including pre-covid. This year’s data, when available, will give an indication if this is a blip or is it here to stay.

This age cohort are likely to want to rent or purchase a home rather than live with parents and thus they add to the pent-up demand.

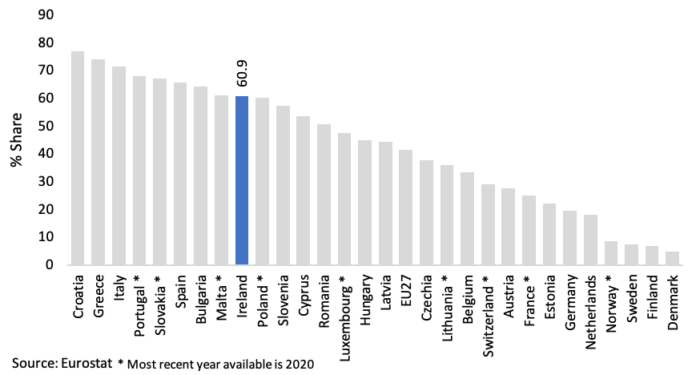

Ireland goes against the trend when it comes to other comparative North and North Western European economies (Fig 1.3). Luxembourg is 47.8 per cent, Belgium is 33.6 per cent, Germany is 19.6 per cent, Netherlands is 18.1 per cent with the remaining Scandinavian countries all reaching sub 9 per cent.

Out of the 32 countries surveyed for this article (who had information available in 2012 and 2020/21), Ireland’s share of 25- to 29-year-olds living with their parents has exploded when compared to other European counterparts (Fig 1.4). During this time, Ireland’s share increased by 26.7 p.p with the next highest being Spain at 10.3 p.p.

All remaining countries saw increases of less than 10 p.p, while ten countries decreased their share (predominantly Eastern European countries).

Another area of potential pent-up demand are those on the social housing waiting list.

In 2021, the Housing Agency estimated that there were 59,247 households – not people – on the social housing waiting list, with 4,170 households being on the waiting list in the Mid West alone.

In 2021, for the Mid West, c. 53 per cent of the main applicants on the social housing waiting list were under the age of 39. The vast majority of those on the social housing waiting list require smaller homes, with c. 77 per cent of those on the waiting list across the Mid West being a one adult and maximum two child household.

This signals the need to directly build smaller social homes for smaller family units rather than increase reliance on the private market through the Housing Assistance Payment (HAP), the Rental Accommodation Scheme (RAS), and other long-term leasing options.

The Strategy Going Forward

Housing for All, the Government’s strategy for dealing with the housing crisis, launched in September 2021. The plan targets an annual delivery of 33,000 per year until 2030. c. 54,000 of these total homes are targeted to be affordable and c. 90,000 are targeted for social homes with the remainder being private or market homes.

This affordability target for housing for all appears to be quite low given the scale of the demand for affordable homes with the total target for affordable homes under Housing for All representing c. 18 per cent of total home delivery to 2030.

Under the latest update for Housing for All (Q2 2022), the plan has committed to delivering 24,600 homes in 2022, 29,000 homes in 2023, and reaching the yearly target of 33,000 homes in 2024 and onwards. Therefore, pent-up demand will continue to build up in the system over the coming years.

Some, not all, local authorities have been given affordable housing delivery targets for 2022 to 2026, equaling 7,550 homes across 18 local authorities. While Limerick is included, Clare and Tipperary have been excluded.

Cork has a target of 567 affordable homes (113 per year), Galway has 377 homes (75 per year), Limerick has a target of 264 (53 per year), and Waterford has a target of 76 (15 per year).

Dublin (all four local authorities) has a target of 5,285 homes which represents 70 per cent of total homes targeted by 2026. By including the Greater Dublin Area (GDA) with Dublin, this rises to 5,813 homes and represents 77 per cent of the total affordable homes to be provided by local authorities.

Out to 2026, it is safe to say the majority share of total affordable homes delivered by local authorities will be heavily focused on Dublin and the GDA.

Limerick Chamber’s pre-budget submission heavily focuses on recommendations for housing with particular focus on the improving and expansion of the Living Cities Initiative, implementation of cost rental homes across the regions, measures to tackle vacancy and dereliction, and an increase in direct build of social homes and decreased reliance on subsidy and leasing schemes.

With the budget being brought forward to the end of September, it will be interesting to see how much housing plays a part given that increased cost of living (of which housing plays a large part) and winter energy demand has also come to the fore of discussions.

The future of housing in uncertain. While data suggests upward trends in delivery, it is not where we need to be.

There are numerous schemes that have been launched to increase delivery and affordability, however, only time will tell if these schemes have the desired effect. Unfortunately, with housing, the past several years of under delivery does not allow Ireland much time.

Seán Golden is the Chief Economist and Director of Policy at Limerick Chamber. Check back soon for the next installment of his views and analysis on issues in housing that impact Limerick and its people.