The outer limits

I was in Sligo the other week. I’d never been there before, never been compelled to visit, but having been summoned there on business, I girded my loins and prepared for the worst. Because I’d heard bad things you see, terrible things; tales of desolation and decline, of charred earth where nothing grows and the locals tussle over carrion with oversized scavengers, chowing down alongside giant crows and two-headed foxes as they fight for survival in a hellish wasteland.

I was in Sligo the other week. I’d never been there before, never been compelled to visit, but having been summoned there on business, I girded my loins and prepared for the worst. Because I’d heard bad things you see, terrible things; tales of desolation and decline, of charred earth where nothing grows and the locals tussle over carrion with oversized scavengers, chowing down alongside giant crows and two-headed foxes as they fight for survival in a hellish wasteland.

I’d also heard that once you went in there, once you exited Mayo, Roscommon or any other place where civilisation still exists, there was no guarantee you’d come out alive, that many a worldly wise expeditionist had ventured into its environs only to mysteriously disappear, eaten up by land, consumed by the terrors that roam Benbulben Mountain and its surrounding territories.

But I hear a lot of things, and most of them aren’t in any way true.

So I set off for Sligo in high spirits, eager to see a new part of the country, to explore this mythical land and put to rights these scurrilous rumours.

But oh my God, what an awful, awful place. The things I’d heard, those scurrilous reports, they were way off the mark, they had inaccurately portrayed not just the county but also its eponymous town. It wasn’t any way as bad as they’d said, not even close.

It was ten times worse.

At this point I should say that if you’re from Sligo and you’re reading this then I can only apologise: I am sorry that you come from Sligo, I can only imagine the suffering you’ve endured.

Jokes aside though, my sojourn to The Yeats County (this is, allegedly, what they call it) was as depressing as it was brief. You may think that parts of Limerick suffered during the recession, that the unfinished Parkway Valley site on the Dublin Road is an eyesore, that there are still too many boarded up storefronts throughout the county, and that more could be done to enliven city centre nightlife on any given week, but it’s only when you see the devastation wrought upon other parts of the country that you begin to appreciate what you have. Because while Limerick still has a long way to go, it is light years ahead of Sligo and the north-west region in general.

And around them, everywhere you look, reminders of the past, of a time when Sligo people had no need to leave in their droves, when there was more than enough to sustain them right there on their doorstep. These old buildings, hardware stores, family-owned pubs, hotels, newsagents, have been left as they were, abandoned by their owners, growing old and grey among the ailing survivors.

It’s only when you reach Sligo town itself that a semblance of normality is restored, but even then there’s an otherworldliness to it all, a feeling that you’re only a couple of factory closures away from a mass exodus, from waking up to find that everyone’s gone and you’re the only one left.

This may sound unnecessarily dramatic, like an unfavourable trip advisor review, but, in the kindest way possible, Sligo encapsulates everything that is wrong with this country.

The recovery Enda Kenny told us to “keep going” has yet to even begin there, and it may never do so. The regeneration experienced in Limerick post-2013 is something the people of Sligo can only dream of. And the things we’re currently getting upset over; post office closures, ghost estates, rural isolation, sub-standard broadband; are par for the course in a county that is being left behind, forgotten about as its denizens flock to already overcrowded urban centres.

But why should we care about what’s going on in Sligo? Haven’t we got enough problems of our own?

Well, we have, but those problems will always be accentuated by the plight of other, less fortunate, counties. For example, Sligo has the lowest rate of employment growth in the country, rising by just 2.2 per cent between 2011 and 2016 – the national average is 11 per cent.

This is nothing new though, ambitious young professionals have always gravitated towards bigger and better opportunities, they’ve always waved those one-horse towns goodbye and made for the big smoke. But whereas in the past they seamlessly slotted into thriving economies, into living quarters designed specifically for their needs, they are now fighting for the privilege of being robbed blind by unscrupulous landlords, their fledgling careers potentially scuppered by the cost of the living, by the Government’s inability to neither foresee nor tackle a housing crisis which had been coming down the line for years.

Such is the exorbitant cost of renting in Dublin and Cork – with Limerick, Galway and Waterford not far behind – many of these highly-qualified, highly-experienced young professionals are being dissuaded from pursuing their dreams, the lure of working in their field of choice negated by the knowledge that more than half their monthly salary will go towards keeping a roof over their head.

And so they return home, back to Sligo, back to that ailing town they’ve called home since the day they were born. But there’s nothing there for them. Yes, there might be jobs, but not the jobs they want, nothing like the jobs they’d applied for in Dublin, the jobs they’d spent four years in college working towards, the jobs they were born to do. There might be accommodation, and it’ll surely be cheaper, but if they take that job they don’t really want, the one that breaks their heart every time they clock in, their wages will be lower too.

And so, after much deliberation, they compromise. They call back that place in Dublin and accept that much sought-after position. They call the local estate agent and say yes, I will move into that flat in Sligo town centre. And they go onto Google Maps and begin plotting the route they’ll take twice a day, five days a week for the foreseeable future, hoping that eventually, with a bit of luck, they might able to move to Longford, Cavan, some other dying town situated within an hour of where they work.

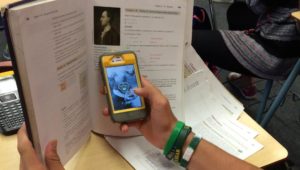

Hi honey, how did your Snapchat exam go?

At least you hope they are.

You hope that they’re paying attention, hanging on the teacher’s every word, resisting the temptation to pull out the phone for a quick look at the umpteen notifications they’ve received since class started four minutes ago.

Most won’t be able to resist, most will risk detention, a dressing-down and more just to get their fix. And who can blame them? Because school is boring, far more boring than a Snapchat story or an Instagram feed. It was boring when we didn’t have smart-phones and it’s boring now. But when we were there all we had to distract us was the back of someone’s head or a dog playing in the yard outside. If we’d had smartphones, and everything they entail, we’d all still be stuck on our twelve times’ tables.

A Bill prohibiting students from using their phones in school was recently proposed in the Seanad. Outlining a system where phones are handed in every morning and returned at the final bell, Senator Gerard Craughwell’s Bill hoped to provide a framework for all schools to work from, defined laws which could be applied without fear of reprisal. However, the proposal received a lukewarm response, its critics likening it to the actions of a “nanny state” and suggesting an outright ban was not the way to go.

Yet in France a similar law has just come into being. Recognising the harmful effects mobile devices can have on a child’s school years, French politicians have wasted no time in banning phones from the classroom, implementing a zero-tolerance policy which will operate throughout all primary and middle schools. And so, while little Pierre and Camille stare stubbornly at their text books, their bored brains subconsciously processing the information contained therein, our lot, our wannabee scholars, will continue to furtively reach inside their pockets in search of something far more interesting than Shakespeare, Pythagoras and that barking dog outside.