Needless to say, the answer was yes. This is a county teeming with writing talent, both male and female. It’s one with writing centres, writer groups and writing workshops, one which actively encourages those with even the slightest interest in writing to nurture that talent and utilise it in whatever way they see fit.

And, just like their male counterparts, the women of Limerick draw upon their homeland for inspiration; it shines through in their writing. Some may no longer live here, others may write about things far removed from childhoods growing up in the Treaty County, but all are of this city, and all were hewn and crafted here.

I spoke to three of them.

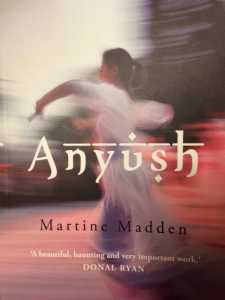

Martine Madden

For an average Limerick person, the thought of leaving the county to settle down in another part of the world is anathema. If pressed they might settle for a dozy existence on some quiet beach in the Maldives, or a penthouse in the heart of Manhattan, but only under extreme duress.

Laois, though? Don’t make me laugh. Yet that’s where Martine Madden, formerly of the Ennis Road and Laurel Hill has ended up. However given the extent of her travels thus far, it’s perhaps understandable that she has chosen to settle in one of the nation’s quieter regions.

Part of those travels included a spell in the middle-east where she, inadvertently, drew stimulus for her debut novel, Anyush. A conversation with a colleague, a woman of Armenian descent, drew her attention to the Armenian genocide, a horrific, often undocumented tragedy that occurred during the First World War.

At the time the story didn’t resonate all that deeply, it was a faraway tragedy from a faraway time in a faraway land.

Upon her return to Ireland however, Martine researched the genocide further and was shocked at what she saw: “The photos were utterly extraordinary, I can remember the first one I saw of a woman and her two children; their bodies lying by the side, they’d obviously died of starvation.”

Writing a fictional account of a hundred-year old event seems like a monumental task for any author, never mind one with no previous published works. But that was precisely what Martine did.

“I write historical fiction because my own life is very boring, very ordinary. But history and researching history and looking at famous figures in history is endlessly fascinating,” she explains.

That fascination led her on a journey almost as long and varied as her time in the middle-east; writing Anyush took eight years.

“Researching takes a long time, between learning to research and learning to write, that was kind of what took so long,” Martine explains.

Included in that timescale was a rewrite designed to make her book slightly more palatable. Early feedback from publishers suggested that war and genocide were “a very hard sell”, one agent responded with the line: “I just don’t know what to do with this.”

However, Martine’s alterations, while helpful in getting her work published, had repercussions elsewhere.

Upon visiting the Armenian community in Dublin, she discovered that the inclusion of a central love story between a Turk and an Armenian was, for the Armenians, “very hard to swallow.”

Worse was to follow.

“There’s a very strained relationship between Anyush, the central character, and her mother,” Martine explains. “I really didn’t know this, but in Armenia mothers are revered, and they found it insulting that I wrote that Anyush had a difficult relationship with her mother.”

Although there were a lot of things in the book that they didn’t like, the Armenians were taken enough by Martine to invite her to give a talk about the genocide. And it was this which eventually won them over.

“I think when they learned why I was trying to write this and I wasn’t just trying to make a quick buck from something so important to them everything changed. And it’s been wonderful actually, it’s been really good.”

Attentions now turn to her second book. Which oft-forgotten historical event is Martine focusing on this time?

“The story in set in India in 1905 and is told from the point of view of a number of characters. What they have in common is they all work for the Viceroy.”

Lore from her previous work features throughout, but whether it will contain a love story remains to be seen.

“There were two pretty full-on sex scenes in my first book, and not only did my daughters read it, but the book club in their school also read it. My daughter, who was in sixth year at the time, died a thousand deaths.”

However that embarrassment was quickly put to one side when Martine brought her daughters to their motherland for one particularly special occasion.

“I won the Kate O’Brien Award and it was presented in the theatre in Mary Immaculate College. It was a fantastic moment as a writer, but also for their girls. Even though they’ve grown up in Laois, they have a real attachment to Limerick.”

That attachment comes from still having family in the area, but also from a city keen to recognise one of its finest writing talents, even if she has left us to seek pastures new.

http://www.obrien.ie/martine-madden

Claire Sadlier

Claire Sadlier fits into the latter category. She still has ambitions, small ones, but having reached retirement age, she can do without the pressure and expectation that comes with being a published author.

Like so many others, Claire had an interest in essay-writing and short stories from a young age, but, as we have learned, real-life has a habit of curtailing even the most promising young writers.

In Claire’s words, her passion for writing “kind of went dormant” as the years went by.

It wasn’t until she reached the age of fifty that she decided to rekindle her love her writing, enrolling in a creative writing course at UL. She wrote steadily for two years but then “lost it again”, neglecting her craft until she retired some years later.

At that point, she joined the Limerick Writer’s Centre and completed a series of short-stories for the delectation of her fellow members.

This resulted in her and some of her contemporaries being published in a special one-off collection commissioned by the Writer’s Centre. Yet, despite that success, Claire isn’t all that interested in a serious career as a writer.

“I think that would put me under pressure, the feeling I had to perform. I’m 65, what do I want all that hassle for? I’ll just write for myself and if it’s published, it’s published and if it’s not, it’s not. I’ll write anyway, you know,” she explains.

Claire’s motivation for writing comes from somewhere else, somewhere much deeper. She’s driven to write by a compulsion, a nagging sense of ennui which can only be banished by the creative process.

“I wouldn’t feel it every day, but I’d certainly feel it if I gave it up again. I would feel that there’s something not right, that I have to do it in order to feel alive.”

This has led her to explore new genres of writing, genres which one wouldn’t automatically associate with someone within her demographic.

“A lot of it is traditional short stories, but I’m writing one at the moment which is more magical realism and I’ve kind of got interested in that. It’s based on Spanish literature, Cervantes. The most fantastic things happen but the tone is completely normal.”

Claire sees this experimentation with diverse themes as part of her education as a writer, an education she is happy to undertake away from the prying eyes of publishers and agents.

However she admits to occasionally sending her work into competitions – if she’s written something she’s especially pleased with.

Although she doesn’t like to admit it, she has an ambitious streak, however small. “I would like to actually win something,” she says laughing, “in some ways that could be off-putting though, you might say to yourself ‘oh I’ve won something, why should I bother’.”

That Claire would ever stop bothering with writing appears highly unlikely. She may not be possessed of the same determination and drive as some of those I’ve interviewed, but her reasons for writing are equally as important, equally as valid.

“I think even if I never got anything published I would stay writing now, just for myself, for my own sanity even.”

I would wager that any writer, from any sphere, can relate to that statement.

Siobhán MacDonald:

Just like her contemporaries, Siobhán MacDonald received that same advice when she graduated from college. She was encouraged to use her love of language and interest in the origins of words in a different field, a field with more security, more job prospects.

So she became a technical writer, spending her days drafting documents, manuals and project plans. Siobhán flourished in this industry, forging a career for herself, spending more than a decade working in a variety of companies across Ireland, Scotland and France.

But while Siobhán was writing and getting paid for it, she wasn’t really writing, at least not in the way she’d envisaged it. She was left in limbo, her desire to write fiction, which had present since her schooldays, constrained.

To this end, she began really writing, penning short stories in the evenings, sending them off to competitions, honing her craft. And, to her surprise, all those years drafting proposals and documents had left their mark.

“When I moved to fiction, the technical writing actually helped in terms of plotting and mapping,” she explains. It helped to such an extent that she quickly progressed to writing her first novel, focusing on the psychological-thriller genre, one where plot and pacing are everything.

That novel was Twisted River, a book that received plaudits the world over when it was released earlier this year; five star reviews from the Chicago Tribune and the Toronto Star sat alongside ringing endorsements from literary heavyweights like Chris Pavone, Siobhán was even compared to Paula Hawkins, best-selling author of The Girl on the Train.

It would appear that it was a seamless transition, that she had changed from one career to the other without pausing for breath, the mistress of all she surveyed. But it wasn’t quite that straightforward.

Siobhán began working on Twisted River in 2007 and, after receiving her fair share of rejection letters, she struck gold; a publishing deal. She had made it. Then things started to go wrong. Her editor, with whom she had built a harmonious relationship, left the publishing house, then the entire company collapsed.

Having already scaled the mountain, Siobhán was forced to start over; just another writer with aspirations. Her misfortune, however, turned out to be a blessing in disguise.

Twisted River was picked up by Penguin and, with their help, quickly became one of the year’s breakthrough hits. Radio interviews, Q & A sessions and appearances at literary festivals followed, she has recently received an offer to tour the States to further publicise the book.

Whether she takes up the offer or not depends on her schedule. Between all the acclaim for Twisted River, Siobhán has released another book, Blue Pool.

Set in County Clare, it tells the tale of three women forced to confront “buried memories and decades-old fears.”

Blue Pool is currently only available in digital format but Siobhán hopes to secure a publishing deal in the coming months.

In the meantime, she continues to work, describing herself as being “three quarters of the way” through her third novel, which she tentatively describes as “the best thing I’ve done so far.”

Such tentativeness is par for the course when writing thrillers: “Readers of this genre are very demanding,” Siobhán says, “you have to grab them, ratchet up the suspense, keep them involved and ensure there’s a satisfying ending.”

In an effort to ensure those reading her work are left fully sated, Siobhán works as rigorously as her schedule allows. Although reluctant to call herself prolific, she admits that she “often has to remind herself to get up and eat” when she’s in the writing groove.

With eight-hour sessions often the norm, Siobhán’s main concern right now is ensuring she maintains her output. That output has seen her release two books already this year, but she is not resting on her laurels. She wants to build upon her success, reach a wider audience and continue to develop her craft. But more than anything else, she simply wants to be known as a “respected crime writer”.

One suspects she has already gone way beyond that.

http://www.siobhanmacdonald.com/home.html