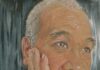

by Alan Jacques

“I WALK like I am dead. I talk like I am deaf. I shout like a dog. Oh, where is my God?”

These anguished words were scrawled on the wall of a small grimy little room in a hostel just off the Dock Road by asylum seeker Abdirahman Mohamed Osman.

And despite the fact that the cramped space he currently occupies does not have bars on the windows, it still feels more like a holding cell than a normal dwelling. There’s an oppressive air and the walls are seeped with misery and dismay.

Before the overthrow of President Siad Barre in Somalia in 1991, and the two decades of anarchy and bloodshed that followed, Abdirahman lived a privileged life as the son of a successful businessman.

He tells me proudly that ‘Osman’s Shop’ was well known by everyone in Mogadishu.

“We had everything; three houses, a big store in the city centre and a boat in the sea. We had a good life,” the 33-year-old asylum seeker recalls.

However, in January 1991 after the fall of the dictator Mohamed Siad Barre’s regime, life in his homeland would never be the same again.

Intense armed conflict broke out in Somalia with different clans fighting and plundering for control of land and resources in the south.

Indiscriminate barbaric acts of murder, kidnapping, torture and sexual violence became part of everyday life. On top of this slaughter, drought and famine also took its toll on this crippled African nation.

An estimated 350,000 to 1,000,000 Somalis died during the insurgency. More than a million people fled its war-torn killing fields and at least two million were left internally displaced during decades of volatile warfare.

Abdirahman’s world was now filled with violence, cruelty and fear, constant fear. Sleep from this day forth would only bring hellish visions and frightening memories.

Worse was to come.

In 1997, a heinous nightmare ripped his life asunder and torments him to this day.

Terror called at 6am when Abdirahman, 15 at the time, and his 17-year-old brother were both woken by their father for morning prayers. The teenage boys were not happy to be woken so early but were soon shaken from their slumber by a heavy knock on the front door. A moment later, there was a heavier knock.

Then the front door was kicked in by a group of 12 ragged raiders armed with Kalashnikov rifles and explosives.

“They lined the three of us up and opened fire,” he tells me, with his throat dry, barely able to speak.

His pain almost 20 years later is still plain to see. He is back in that room again as he is every time he closes his eyes at night. He is forever haunted by this terrifying experience.

“My brother and father were both killed. After the gunmen ransacked the house, they left. My mother, who is a nurse, found me and saw that I still had a pulse. She got me medicine and hid me in a cowshed.

“My brother was my best friend. The men who shot us were from the Hawiye clan. They killed my brother and my father because we were from the Reer Xamar clan.”

How Abdirahman survived this attack is nothing short of a miracle. His body is riddled in bullet holes. The scars on his arms, legs, chest and neck give testimony to the horrors he has seen. He asks me to feel the back of his neck where a bullet is still lodged under the flesh.

“It was hell. I still need medicine just to sleep. I have nightmares all the time,” he says.

However, Abdirahman’s nightmare did not end at the muzzle of the Hawiye clansmen’s guns.

When they discovered that the teenage boy survived the attack, they returned to his home and kidnapped him.

To raise the ransom money, his mother sold their family home to get him back. Then, in 2002, she paid traffickers to get her son to safety. He travelled on a false passport into Kenya and onto the UK.

“I had no English and I arrived in London with a pair of sandals on my feet and a light summer shirt. I had never experienced such cold weather before. I had a fake passport and the man I travelled with left me on a street in Southall and never returned.”

In 2015, little has changed, and that cold and frightened refugee still feels lost on a strange street corner not knowing which way to turn. He was refused asylum in the UK in 2006 and has been in Ireland ever since.

“I had no passport. Nobody had passports. We all escaped Somalia through agencies, but of course I am from Somalia. They rejected me in England on the grounds I travelled on a fake passport.

“If I am not a refugee, then no one is. I escaped from hell and I am still in hell. I am in limbo. I don’t see any future and nothing has changed. I am trapped, not able to move forward with my life. My situation has not changed since I left my home and family.

“I do not want benefits off the Irish Government. I want to be able to pay my own way. I want to be able to finally start a life here after 14 years of hell. I feel for the refugees from Syria, but we have been here for over a decade and nothing has changed.

“I feel I will rot in this little room. I will die here without any change.”

A well-loved singer amongst the Somali community in Ireland and across Europe, music is Abdirahman’s only refuge. It is his life. He can be found on YouTube under the name ’Yugrayn’ putting his heart and soul into expressing his frustrations, his anger, and his grief.

In fact, such is his popularity that he has been invited to perform in countries around Europe and he dreams one day of living an ordinary, productive life, where he can interact with the world on his own terms.

Abdirahman feels he has been forgotten by the Irish Government. He is angry. Having met the man, I am angry too. We should all be angry about the plight of Abdirahman Mohamed Osman. He has suffered enough.